Jean Campbell presented the life and work of Antonio Dattilo-Rubbo for the retrospective exhibition at the Manly Art Gallery & Museum from 5 December 1980 to 18 January 1981.

This is her introduction to the exhibition catalogue.

The article shows how Dattilo-Rubbo influenced a whole generation of Australian artists, and how his enthusiasm for art led to the foundation of the Manly Art Gallery & Museum, and last but not least, pays tribute to an extraordinary mentor.

Il Cavaliere Antonio Dattilo-Rubbo died 25 years ago at the of 85, yet until now there has been no tribute, neither exhibition nor publication, in recognition of the significant role he played in the development of art in Australia in the first half of the 20th century, both as a painter and teacher.

This neglect is only understandable when we remember that Dattilo-Rubbo’s oeuvre was not large and that his reputation as a painter was built on the kind of academic, genre, story picture in vogue at the turn of the century, but considered ‘old hat’ and swept hastily under the mat in the eruption of new art forms in the 1950s; also that by the time he died most of those adventurous students to whom in the early, difficult decades he gave tremendous encouragement and support were widely scattered around the world, or themselves regarded as outmoded, ageing and only belatedly struggling towards recognition.

In his long life Dattilo-Rubbo held only one one-man exhibition of any significance, an exhibition of 130 paintings and drawings in Melbourne in 1919. Two smaller exhibitions, held in Sydney and Brisbane in 1949 as fundraisers for the Manly Art Gallery, a project dear to his heart, did little for his reputation, though they evidenced in a convincing way his character and total involvement as a crusader for art. As the Sydney Morning Herald critic of the day commented: “In his exhibition at the Macquarie Galleries he gives a practical demonstration of an active interest which refuses to accept the sluggish customs of officialdom. He realises that if art is to be fostered, it is useless to rely solely on petitions to governmental departments or letters to the press. One has to go out and do something oneself to the best of one’s ability – one’s example may bear fruit, however forlorn the hope.” (SMH, 9 March 1949)

There were two interdependent factors limiting Dattilo-Rubbo’s production, and also probably development, as a painter. In a period when picture sales and commissions in Australia were few, his need to earn a livelihood for himself, his wife and family drove him to spend long hours teaching. For years, he taught four nights a week and every day but Sunday, and this, with his commitment to the Royal Art Society, was obviously restricting: ‘My leetle boy, ‘e can eat’, Lloyd Rees reports him regretfully saying, when a group of more experimental artists asked him to lead them in the formation of a new art society in 1919, and, wrote Lloyd, ‘saw the point’. (Lloyd Rees, The Small Treasures of a Lifetime, p. 76, Ure Smith, 1969)

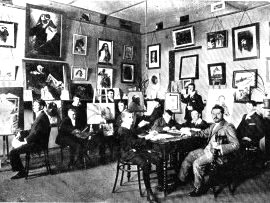

A natural teacher

Also Dattilo-Rubbo discovered himself to have charisma as a teacher; his students adored him and undoubtedly he enjoyed teaching - ‘brilliant’, ‘great’, ‘marvellous’, ‘fantastic’, ‘sympathetic’, ‘inspiring’, ‘a colossal teacher of drawing’ is how students remember and describe him (tapes of interviews with artists by Prof. Sydney Rubbo, 1969, are held by the Art Gallery of NSW). The ‘Signor’, as they affectionately called him, knew the true meaning of education; he was able to draw forth from his pupils the best they had to give, leading them, through his knowledge and enthusiasm, to a new awareness of themselves, their potential, and what art is about. Whether at secondary schools – and he taught at several around Sydney – at the Royal Art Society classes or in his own Atelier, Dattilo-Rubbo’s warmth of spirit, flexibility of mind, backed by sound knowledge and discipline of draughtsmanship and the painter’s craft, made his enthusiasm infectious, and the art lesson an exciting challenge.

As early as 1902 Dattilo-Rubbo had advocated the importance of inculcating in youth, love and admiration of art. In a letter to the press he wrote: ‘I would like the government of this country to adopt the system of the Continent – that is to have the study of drawing made compulsory in all schools and colleges of the state and to have hung on the walls besides the maps, a few specimens of the best pictures.’ (Evening News, Sydney, 4 April 1902).

Dattilo-Rubbo’s teaching life lasted 43 years, many of Australia’s notable artists passing through his studio. During this time he regularly contributed his panel of paintings to the Royal Art Society of NSW or the Society of Artists’ exhibitions, sometimes to the Australian Watercolour Institute exhibitions, and his work was also included in various important mixed exhibitions both in Australia and overseas, in London, Paris, New York, Naples. In his younger days purchases were made for state collections in Australia and New Zealand, but for years now, except in the Manly Art Gallery, his paintings and drawings are rarely shown. Moreover, his reputation as a teacher has faded and the exuberant and explosive personality that to those who knew him made him ‘the personification of a true artist’ (The Red Funnel, Australian Painter Series, No IV, October 1906. Illustrated article on Dattilo-Rubbo) is almost forgotten.

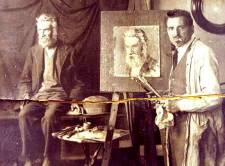

There are signs of re-assessment; some important works have recently been acquired for the Australian National Gallery and interest is beginning to be shown by other collectors. However, it is only by assembling an exhibition such as this, bringing together oils, watercolours and drawings from all periods of his life, works by some of his outstanding pupils, portraits of the maestro from the hands of some, that we can revive the memory and do justice to Antonio Dattilo-Rubbo, to see him as he appeared to fellow artists, working with his students in alert camaraderie – ‘full of enthusiasm, living only for his art, a man of high ideals and generous impulses, with the vital spark of genius flashing out’. (The Red Funnel, as above)

There has been some confusion in reference books and catalogues as to the correct spelling and form of Dattilo-Rubbo’s name. As late as 1949, in the artist’s handwritten biographical details furnished to the Art Gallery of NSW, he signed himself A. Dattilo-Rubbo and the hyphenated signature, usually in printed letters, appears clearly on most of his pictures; very occasionally his work is signed with the initials A.D.R.

An Italian comes to Sydney

Antonio Salvatore Dattilo-Rubbo was born in Naples on June 22, 1870, the son of Luigi-Raffaele and Raffaela Dattilo-Rubbo. His father died when he was a baby and his mother carried on the family mercantile business. Young Antonio showed early a talent for art, won a drawing prize at fourteen, and began his art training at the School of Fine Arts in Rome, where he obtained a certificate of draughtsmanship. After interruption by military service, during which he won favour with the soldiers by drawing their portraits and more importantly had the opportunity of visiting the great galleries of the principal cities of Italy, the young man returned to Naples.

For six months he tried vainly to adjust to business life with his mother, then joined the Academy School in Naples, where four years later he was awarded his Diploma by the Italian Government.

Training in Italy was realistically academic and aimed at the production of portraits, genre and historical pictures, much in demand at the time. But Dattilo-Rubbo’s painting teacher, Domenico Morelli, had been a member of a group known as the Macchiaioli, whose members were aware of 19th century developments in Paris and were influenced to some extent by the romantic realism of Millet and Corot. They were already taking an interest in the effects of light and atmosphere; in Rome also the young Antonio would have been familiar with the work of Giovanni Segantini, who had evolved a style of his own, which approached the divisionism and the vibrant brushwork technique of Seurat.

Although Dattilo-Rubbo’s painting was dark and academic on his arrival in Australia and it was these portraits and genre paintings, with their skilful craftsmanship and sound drawing, that gained him immediate acceptance by the art community in Sydney, the seeds of experimental development and interest in colour had already been sown.

Antonio Dattilo-Rubbo arrived in Sydney in 1897. George A. Taylor in his book of reminiscences, Those were the Days, written in 1901, described him as ‘a jovial Italian, who had popped into Sydney unheralded, but his pictures pulled him into public recognition and his merry personality pulled him into Bohemian affections’.

His arrival was certainly unheralded; not even he, as the story goes, had realised he was coming to Australia. There are several romantic versions of why he hastily departed from Naples – he was jilted, he had taken a shot at someone, he had fallen in love with Australian girls he had seen. Common to all versions is that he had jumped the first boat available in Naples, only to find, when well at sea, he was bound not for America, as he believed, but for ‘Orstralia”.

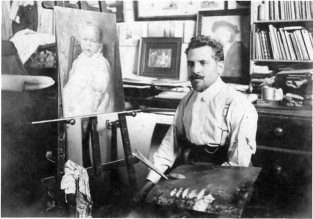

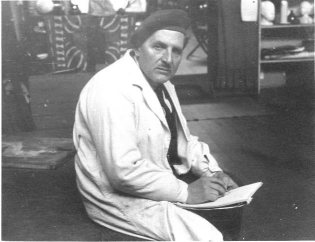

Though short, Antonio was a dashing, strikingly handsome figure, with his dark moustache, Vandyke beard, strongly curling hair, his liquid brown eyes, warm, vivacious manner. Girolamo Nerli, when he painted him in 1899 – a picture which won Nerli much acclaim in the Art Society Annual Exhibition – certainly depicted him as the archetype of the Bohemian artist of the nineties, and the gay Antonio was quickly accepted as a member of the Supper Club and the Brother Brushes of Bondi, a group that included Leist, Souter, J.S. Watkins, Norman and Lionel Lindsay, as well as George Taylor.

These aspiring young artists made a lark of living on the smell of an oil rag, but, in fact, they had little choice. Black and white work, cartoons, illustrations to papers and magazines, provided scant bread and butter for most; the alternative was teaching. Dattilo-Rubbo’s sound and serious training in the Academies of Rome and Naples scarcely fitted him for the journalistic comment of newspaper work, and as he had no English, he would have had at least initial problems with language, customs, and way of life in the strange, raw country in which he had landed himself. But he had his Diploma and he could teach and in 1898 set up his own school. That he managed quickly to establish himself against the strong, established opposition of Julian Ashton’s School is remarkable in itself.

He exhibited a panel of his work with the Art Society of NSW in 1898 and no doubt the purchase the following year of one of his paintings, ‘The Veteran’, for the National Gallery of NSW, contributed to his status and acceptance in the community. J. de Libra in the Australasian Art Review of 1 September 1899 described this picture as ‘a singularly forceful masterpiece’.

In 1900 he was appointed master in the Art Society School and also visiting art master at St. Joseph’s College, Hunters Hill and Scots College, Rose Bay. He also later taught at the Cambridge School on Parramatta River, Kincoppall and Rose Bay Convents.

Art journey to Europe

In 1906 Dattilo-Rubbo wrote to G.V. F. Mann, then director of the National Art Gallery of NSW, announcing his intention of re-visiting Europe and investigating teaching practices in Paris, London, Glasgow and other centres; he also made the suggestion (which was turned down) that he be authorised to spend thirty pounds to purchase for the gallery a selection of overseas student work as stimulation for Australian art students. When the gallery acquired a painting by Maggi, a pupil of Segantini, Dattilo-Rubbo wrote requesting the picture should be hung on eye level, so that students could closely examine the impressionistic technique.

The European visit was a valuable experience, heightening the artist’s aims and prestige as a teacher back in his adopted country. In August 1908, at the annual banquet of the Royal Art Society of NSW (it received its Charter in 1903) public dignitaries, artists and distinguished patrons hear the then-resident, Mr. Lister Lister, report on Signor Dattilo-Rubbo’s ‘recent careful investigation of methods of instruction and best modes of teaching’ in Paris and London, and the re-organisation of classes at the R.A.S. School that followed his return. ‘Classes’, he said, ‘were now going ahead rapidly and in twelve months hoped to see the number of students doubled’. (SMH, 31 August 1908) The Brothers of St. Joseph’s College in their annual magazine also announced proudly a similar upgrading of their classes and studios under the enlightened tuition of Signor Dattilo-Rubbo.

He was, in fact, in advance of his times not only in his own teaching but in his awareness of Australia’s real needs in art. In a long article in the Sydney Morning Herald in 1908, Dattilo-Rubbo stressed the need in Australia for an appreciative public, for general art education, for the establishment, in addition to Fine Art Schools, of an Applied Art School, which would train those of artistic talent to be what he called ‘useful artists’. ‘It is generally thought’, he wrote, ‘that sitting at an easel or modelling a bust is the only means of following an art career, but in Australia there is no demand for the work which has cost the artist so much labour and pains.’ He instanced the way in which Italian cities had blossomed with a rich art heritage through their artisan artists, and how in Naples, Rome, some Australian and English cities, art training was currently being provided with direction towards applied as well as fine art.

‘Mother nature has favoured this land with artistic natural subjects which are unknown, or, at any rate, not yet exploited by our local artists,’ and, he reiterated, ‘what we need in Australia is a good school of applied arts, whether national or Art Society matters not. Such a school is necessary, which may truly claim the name of Australian, unique, typical of its own, a school which would produce the breadwinner artisans, the most useful artists, the art which is needed for Australian progress. We shall then no longer have the overcrowded ranks of artists producing thousands of unsaleable canvases annually.’

While he deprecated the fact that New South Wales had no travelling scholarship to offer experience overseas, he queried the value of ‘that expensive institution’, the Melbourne Gallery School, because its ‘paid scholarships have made exiles of their lucky winners, victims to whom is denied their native soil. … The hopeful student of yesterday is the downhearted artist of today,’ he declared. ‘The last example of want of substantial appreciation was in the exhibition of Phillips Fox’s works – he had to re-pack nearly all his works.’ (SMH, 19 September 1908).

Dattilo-Rubbo’s 1908 prognostication of the disastrous effect on art in Australia of lack of public appreciation and government support of local artists was fully justified; Phillips Fox returned to Europe, adding one more to the band of expatriates that included John Peter Russell, Rupert Bunny, Tom Roberts, Kate O’Connor, Bessie Davidson, Bessie Gibson, Thea Proctor, George Lambert, Max Meldrum. There is no doubt that the almost enforced defection of nearly a whole generation of talented Australians retarded considerably the development of art in this country. Dattilo-Rubbo remained in his adopted country and taught; a small, but not still voice. Although his trip was principally to keep abreast with teaching methods, it enabled him to further his understanding of more recent developments in art.

In London, apart from visiting galleries and schools, he was a guest of John Longstaff, Tom Roberts and Frank Brangwyn, whose strongly designed, colourful painting aroused his lively interest and admiration. For three months he painted in Paris, becoming familiar with the experimental work being done there, and he also visited Venice, where the 7th International Exhibition was in progress, more than 16 nations exhibiting. On his return to Australia, Dattilo-Rubbo waxed lyrical about the setting of ‘la grande festa d’arte’, advocating the advantages of Australian participation, asserting Venice would welcome an Australian pavilion and offering to do all in his power to bring this about.

Taking strong impressions to Australia

When in 1912 Roland Wakelin, a young New Zealander of 25, arrived in Sydney, determined to pursue a career in art, he had already seen Dattilo-Rubbo’s work in Dunedin. In 1913, working as a clerk during the daytime, Wakelin attended Royal Art Society classes at night, where he studied with the Signor, through him meeting Roy de Maistre, Grace Cossington Smith, Neil Gren and Norah Simpson. When Norah Simpson, one of Dattilo-Rubbo’s talented private students, returned from study in Europe that year, with colour reproductions and news of Post-Impressionism and the tenets of teaching of Cezanne and the New English Art Group – of Gilman, Spencer, Gore and Ginner – the Signor was as excited as his students and invited members of his Royal Art Society class to meet her in his Atelier. There also, students could pore over magazines – Studio, Colour, Jugend – become acquainted with the theories of synchromism, discuss the primacy of colour and dynamism in art, the writings of the American Macdonald-Wright. Here, in this lively, questioning climate developed the first coterie of Australian ‘moderns’.

Dattilo-Rubbo not only encouraged his students in the exploration of colour and light, introduced them to the revolutionary work of Van Gogh, Gauguin and Cezanne, but himself, particularly in his landscapes, used high-keyed colour with luminous, staccato, broken touches, approaching pointillism, as in such ‘plein air’ impressions as ‘East Esplanade’, Manly’, 1917, and ‘Manly’, 1918. As early as 1910 in ‘The Moroccan’ he ventured a daring blaze of colour, also demonstrating his admirable, structural and fluent handling of watercolour.

As early as 1914 Dattilo-Rubbo had a lecture on ‘colour harmony’ at the Art Society’s rooms in Pitt Street, discussing the scientific and artistic theories of colour and light behind the Impressionist approach.

Dattilo-Rubbo used a range of colour more vivid and joyous than commonly taught in those days in Australia; he found colour in shadows as did the French, Scottish, English Impressionists. ‘Get rid of the brown,’ Grace Cossington Smith reports him insisting. ‘See the thing as a whole, do not concentrate on one portion.’ (Tapes of interviews with artists by Prof Sydney Rubbo, 1969) Lloyd Rees opined that Dattilo-Rubbo and Roland Wakelin painted the first truly Impressionist landscapes in Australia.

Standing up for his students and their work

The Signor was militant in support of the experimental work of his students. He fronted up to the perturbed elders of the Royal Art Society in defence of their use of heightened colour, stippling touches, cubistic simplification of drawing; he even went so far as to challenge to a duel – pistols, swords of fisticuffs – a particularly prejudiced member, Charles Tindall, when the Society rejected Wakelin’s work for hanging in 1915. Fencing being the Signor’s recreation, this might have become a bloody confrontation; however, the virile little Italian won the day, without violence as Wakelin records, and in 1916-18 the work of the group was accepted and hung in annual Society exhibitions.

When in 1919 de Maistre and Wakelin at Gayfield Shaw’s Gallery combined in an exhibition of their work based on the music-colour theories and harmonising colour charts de Maistre later patented, Dattilo-Rubbo was on the platform speaking in encouragement, while his great rival teacher, Julian Ashton, up from a sick bed ‘to put these young fellers in their place’, glowered from the audience, finally asking in exasperation: ‘But what I want to know; is it beautiful, Mr. De Maistre?” De Maistre’s: ‘I think so, Mr Ashton,’ was the retort courteous and irrefutable. (Lloyd Rees, The small Treasures of a Lifetime, pp 92-3, Ure Smith, 1969)

But although Dattilo-Rubbo encouraged his students in the search for colour, vibrancy and light, emphasis in his teaching was always on draughtsmanship and craftsmanship. In 1912, he, himself, was awarded the Sir James Fairfax Prize for pencil drawing, and among his students have been such notable and diverse draughtsmen as Arthur Murch, George Finey, James Flanagan, who won a high reputation in America, and the irrepressible Donald Friend. Friend acknowledged that Dattilo-Rubbo had driven him to really look at what he drew and to purify his forms. ‘Aha, Donaldo, always the barocco! Rub it out, boy!’ the Signor would command. (Robert Hughes, Donald Friend, p. 22, 1965).

The Royal Art Society could not find fault with his strict foundation of drawing. Beginners drew from casts – stylised ivy or acanthus leaves in low relief, the anatomical horse, the skull, head, hand; drawings were done chiefly in charcoal. From this they graduated to the life class and the Signor was always around with his feather-duster and the scathing, jocular comments. ‘No good! Make laugh the fowls,’ he would declare as the feared feather-duster swept away the unacceptable effort and the deflated student had to start again.

Wakelin, thought by many to have been the Signor’s favourite student, recorded: ‘I often gnashed my teeth, but loved him just the same.’ (Tapes of interviews with artists by Prof. Sydney Rubbo, 1969) A long friendship of mutual respect developed between the two men. Dattilo-Rubbo had no patience with slovenly work, and swift dismissal for the frivolous or untalented student: ‘Better be a tram conductor’; ‘Better darn the socks’, he would announce.Mildred Jobson, who became his wife, was one who took his advice, left the class and became a nurse. After a determined wooing, she married the volatile maestro in 1904.

Despite his uncompromising criticism of their work, the Signor maintained a warm and sympathetic understanding with his students. Elsa Russell, a part-time student of the 1930s, records: ‘The atmosphere of his studio seemed always to be charged with electricity, which of course was due to the vital sparkle of his wit and personality and highly explosive temperament, somewhat peppery, yet always charming.’In fact, he was held to have the power to ‘charm a brass monkey off a tree’, at all times, and it seemed as though his many students were as equally held by the warmth of his personality as by his great knowledge of art and profound philosophy of life. He demanded of young painters the utmost seriousness in their approach to painting.

He had pet names for many of his women students – Cossington Smith was ‘Mrs van Gogh’ (reference to her early painting on the theme of Van Gogh’s yellow room); Alison Rehfisch was ‘Gorgeous’ (her favourite word); Dora Jarret, ‘Sweetheart’, Margaret Coen ‘Gunner’ (she would go boom sometimes!). Irene Meagher, ‘Titianella’, Notable among them were Betty Morgan, a favourite model as well as student and for a time assistant teacher; Janna Bruce, ‘Brucie’, who joined the Bligh Street studio in 1925 and later taught in the school; and Frances Ellis, a New Zealander, for many years pupil, teacher, friend, who took over the organisation of his school and house in his later, failing years. All rallied to his aid in trouble; he was respected, loved, fussed over by them all, particularly after the death of his wife and in the decline of his health; they drove him home after classes and generally saw to his welfare.

Even in old age the charisma of the Signor was still felt; Earle Backen recalls how, when in the 1940s he attended the A.D.R. School, as it was known when Dattilo-Rubbo visited only on a Saturday morning, the obviously very physically ill old man impressed students by his strong personality, as the image of ‘a nineteenth century romantic person’, the Bohemian artist.

By that time Dattilo-Rubbo had joined the ranks of the reactionaries. ‘No more, Mr. Moore!’ was his comment on the touring Henry Moore sculpture exhibition. Indeed as early 1937 he came down firmly on the side of tradition in art in a lecture at the Manly Art Gallery, entitled ‘A straight talk on modern art’. He attacked the ‘modern ‘isms that are lowering the value of art in other parts of the world’ (The Manly Daily, 20 Nov. 1937) and asserted that Australian art should develop with a purely Australian outlook. Like many of his generation, who had welcomed the break from dark, rigid academism and the advent of light, colour and expressive concept in painting, he saw later movements as distortion, encroaching ugliness, threatening, destructive of the aesthetic ideals he had all his life regarded as the meaning and goal of art; commercialism he saw as perhaps the greatest menace.

Dattilo-Rubbo's artistic development and recognition

1919, when he was in his fiftieth year, must be seen as a high point in Dattilo-Rubbo’s painting life. He ventured interstate, was received with considerable respect and his work was purchased for interstate collections. He was represented by a panel of portraits and landscapes in the Federal Exhibition in Adelaide, where the critic described him as ‘a painter who has gained considerable fame in the Eastern States’, (Adelaide Mail, 22 Nov. 1919), praising his conservative portraiture in preference to the more experimental landscapes.

In December that year he mounted a large one-man exhibition at Decoration Galleries in Collins Street, Melbourne. Probably he hoped for a more sympathetic attitude to the broken colour and Impressionist technique employed in his landscapes and the more colourful approach creeping also into his portrait and figure work.

If so, he was disappointed; praise was lukewarm and chiefly for his more academic portraiture, whether in oil, watercolour or charcoal. The Melbourne Herald critic opined: ‘In ‘Pea Gathering, NSW’ there is evidence of much sincerity of purpose, but certain essential qualities have been overlooked in the endeavour to be truly descriptive. In his studies of old men Mr. Dattilo-Rubbo shows singular grasp of technique together with a sympathetic sense of quality and the significance of old age.’ The critic also commented on ‘the fresh painting of landscapes and seascapes out of doors’ but concluded that ‘sometimes treatment is too inconclusive and colour too crude to be acceptable.’ (Melbourne Herald, 17 Nov. 1919) The Age critic concurred: ‘His style is that of modern French Impressionism, very high in tone and with a somewhat spotty technique that is obtrusive in its mannerism at times.’’ (The Age, 19 Nov. 1919)

This was almost an echo for Sydney’s reception of his panel of paintings in the Annual Exhibition of the Royal Art Society in the previous August. ‘A. Dattilo-Rubbo,’ observed the Sydney Morning Herald critic, 'continues on his impressionistic way and his views of railway embankments and orange-hued clay cuttings will no doubt delight those who prefer a little ginger in their colour harmonies. A canvas which stands out from the rest is a forcefully painted portrait of Miss Irene Hope Meeks. The green-grey accents on the lighted cheeks may be taken exception to but the drawing and modelling reach a high standard of excellence.’ …’This artist affects a realistic, uncompromising style of an experimental character in ‘The Mountain Train’. Herein the palette knife is freely used and a glaring colour scheme is adopted to express the effect of light upon the sheer side of the hill, above which the train emerges from a cutting. As one might expect, there is a vast amount of cleverness and it will be freely discussed. He will find more admirers for his Australian landscape with its suggestion of drought and dust.’ ((SMH, 22 Aug 1919).

The Bulletin remarked, after some hedging criticism, that Dattilo-Rubbo was using three different styles and observed with some percipience that ‘something seemed to be worrying him.’ (The Bulletin, 28 Aug 1919) Undoubtedly rejection of his more experimental work was worrying him. ‘We were repeatedly told’, wrote Wakelin in 1928 in an article ‘The Modern Art Movement in Australia’, ‘that we were ‘on the wrong track’ and really wondered if we were, and, I think, unconsciously drifted in some degree back towards the academic.’ (Art in Australia, Dec. 1928) While youth and further experience overseas strengthened the purposes of Wakelin, de Maistre and Cossington Smith, in the Signor, harnessed to his heavy teaching commitments, the spark of adventure was slowly suffocated.

Recognition and success continued into the twenties. In 1922 he was made a Fellow of the Royal Art Society of NSW, one of the first eight; he was also appointed to advisory committees in the initial stages of planning of the Australian War Memorial and the Art School at the East Sydney Technical College, which, in total opposition to Julian Ashton, who condemned the idea of a Government Art School outright, he supported. He was also a participant in important Australian and overseas exhibitions, and his Atelier moved to Hudson House in Bligh Street, flourished and continued to attract the more forward-looking younger artists.

Probably for Antonio Dattilo-Rubbo the culmination of his career was the honour bestowed on him in 1932 when for services to art he was created a Knight of the Crown of Italy, entitling him to prefix his name with Cavaliere; in this he took a naïve and natural pride that rejoiced his friends. An exhibition of his students’ work the following year was also a source of pride, an exhibition Dr. Lloyd Rees remembers as holding more vitality and interest than that of the Julian Ashton School the previous year.

Changing times

But the clouds began to gather. He quarrelled with the Royal Art Society, and no longer a teacher with that Society, joined the Society of Artists in 1934. Rivalry between the two Societies at this time was running high, but Dattilo-Rubbo never held the position of importance in Sydney Ure Smith’s Society of Artists as he had in the Royal Art Society through the most vigorous years of his life.

Tragedy struck hard when in 1933 his beloved son Mark, at 16, died of meningitis. His elder son, Sydney, a brilliant microbiologist, married in London and returned to live in Melbourne, where he was a professor at the university. Sydney Rubbo's wife, Ellen Christine Rubbo 1911-1977, became a well-known painter in her own right, and was a member of the Melbourne Contemporary Artists Group. Their children: Michael, Mark and Kiffy, went on to have careers as a filmaker, the founder of Readings book retailers and the Director of the Ewing-Paton Galleries, respectively. CW - March 2011

Dattilo-Rubbo was also bitterly hurt when, at the outbreak of World War II, the country of his adoption, which he had served so well, put him in an internment camp. He was released after a short period, and wrote to the secretary of the Manly Art Gallery, to which he had recently made a gift of 100 of his pictures: ‘After an unpleasant waiting for an inquiry about my political activities, my innocence, has proved as usual the protection of British Justice and I am home, as free and loyal subject of my adopted country, which I love more than the one where, by accident, is (sic) born. I feared nothing, and I may add, that my usual generosity and social life brought upon me the suspicion of disloyalty, I believe; through my Title, and then a donation to an Italian club of one of my works and a monetary contribution towards furnishing it.’ (letter to Mr Marriner, Secretary Manly Art Gallery, 18 June 1940)

Despite this, in 1942 he wrote offering himself as a war artist for the execution of portraits, an offer which was acknowledged with tardy thanks; possibly the commission to paint the posthumous portrait of war-time Prime Minister John Curtin, in 1947, was a belated result of this. The portrait is a soundly constructed likeness, if a rather dark and dull painting.

Dattilo-Rubbo was indeed generous; apart from his considerable gifts to the Manly Art Gallery, not only of his own work, but that of other well-known Australian painters and famous casts from the antique, he made gifts to the National Gallery of NSW, to several schools where he taught, and donated 50 paintings to the Red Cross.

Through the 20s and 30s there had been a gradual return to a more academic approach; firm drawing, realisation of tone – emphasised for a time by the influence of Meldrum – were basic, as in his dark, early genre paintings. But subjects were drawn more directly from life around him, at home, in the studio, the near coastal landscape; colour remained brighter, more high-keyed, brushwork broad and even dashing use of the palette knife.

In the 1940s, when he was no longer tied by the demands of the school and had recovered from hospitalisation, there was a brief return to the lyricism, the broken colour of the vital impressionist period. In ‘Sun Spots’, Jean Morgan, the new, youthful model, is seen with freshness, subtlety of colour and sensuousness of paint; in ‘The Artist and Model’, there is a sweetness and sensitivity of colour and form, rare in the work of the preceding years. The slender, half-draped form of the young girl, her face reflected in a circular mirror, is balanced in the composition by the seated figure of the ageing artist, grey, tired, looking out past his easel down the vista of the years; there is story and symbolism in this picture, as in his early work, but it is not merely a subject picture, it is personal, deeply felt, expressed with the sure touch of long experience and knowledge. Old age yearns for youth, beauty, for art, for the unattainable.

The release from the years of teaching had come too late; shocked by the sudden, tragic death of his wife in 1943, and suffering from a heart condition, he was a sick, lonely old man. His status as a painter and teacher had declined; illness had forced him to abandon many of his activities, including membership of the Manly Art Gallery Committee; his work was disregarded and he felt bewildered and alarmed by the kind of art that was being accepted and promoted.

His School, which he had handed over to Frances Ellis when he relinquished it in 1941, was taken over by G.F. Bissietta in 1949, and Bissietta’s ideas of teaching and of art were completely at variance with his own. With the assistance of Janna Bruce, Bissietta maintained the School for some years, but it never recovered the significant place it held under the now out-dated Signor. Bissietta did, however, with the assistance of the Dante Alighieri Society, gather together a group of work of Cavaliere Dattilo-Rubbo in 1955, immediately after his death, for a small memorial exhibition in the Bissietta Gallery.

Happy years in Manly

In the early years of their married life Antonio and Mildred Dattilo-Rubbo (left in 1943) lived at various addresses around North Sydney. A son, Sydney, was born in 1911 and five years later the family moved to Manly, where in 1917, a second boy, was born. They stayed in Manly until the final move in 1927 to ‘Vesuvio’, in Prince Albert Street, Mosman, where adding a studio to the existing house in 1936, the artist continued to live right up until his death.

The eleven years at Manly were halcyon years, productive and successful. The home life was a happy one; Dattilo-Rubbo, like most Italians, was fond and proud of his sons; he was also fond of good food and wine; there were many friends, companionable students, laughter, real Italian hospitality. During this time he gathered about him that lively group of students with whose adventurous impulses he could and did identify.

The picturesque coves and beaches and the bush around Manly were the scene of many of Dattilo-Rubbo’s most delightful, plein air impressionist paintings, and his fondness for the area and dedication to art education made him an instant and energetic supporter of the proposal put forward in February 1924, that Manly should form an Art and Historical Collection of its own.The idea grew out of a suggestion in 1923 that the painting ‘Middle Harbour from Manly Heights’ by James Jackson, prize winner of an art competition organised by Mr. J.R. Trenerry, editor of the Manly Daily, should be acquired by public subscription to hang in the Town Hall.

The acquisition of this picture was the beginning of the collection. A Dattilo-Rubbo and Charles Bryant, the marine painter, were appointed to the first Committee, which was headed by the Mayor and consisted mainly of citizen members, and both artists immediately made a gift of a painting and persuaded many of their artist friends to do likewise. Hung in the Town Hall, the collection grew rapidly; interested members of the public made gifts and occasional purchases were made, and the Council decided to make available and adapt the pavilion at the western end of the Harbour Beach as a permanent Art Gallery.

One June 14 1930 the Manly Art Gallery and Historical Collection, with 200 exhibits, the first institution of its kind in the environs of Sydney, was officially opened by His Honour, the Chief Justice, Sir Phillip Street.

Despite his busy life, Dattilo-Rubbo maintained his interest in the little Gallery, adding to his gift from time to time, attending meetings, sometimes helping with the organisation of exhibitions, lecturing, giving advice on the quality of gifts offered. In 1939 he offered 100 of his works, some works by other artists, and a group of sculptural replicas, provided the Council would provide a room to house them. This offer was gratefully accepted and in 1940 the Dattilo-Rubbo annexe was built. Dattilo-Rubbo contributed funds towards the Gallery and also in his will left a sum of money to be used towards maintenance and preservation of the collection.

In recent years with state as well as municipal assistance the Manly Art Gallery has been again enlarged, lit and air-conditioned. The collections have grown steadily and a director and strong band of supporters make it today an active art centre. Dattilo-Rubbo would no doubt view with pride and pleasure and would certainly be much gratified by the honour and recognition accorded here to his work as painter and teacher.

PS: A very personal view of Antonio Dattilo-Rubbo is recorded by his grandson, Mike Rubbo, in his blog of 10 March 2008.